Utopian Scholastic: The End of History and the Rise of Agency‑Driven Education

The piece revisits the late‑1990s design aesthetic dubbed Utopian Scholastic—defined by photo‑rich collages, flat typography and a technophilic optimism—and traces its footprint in early CD‑ROM encyclopedias, video games and the user‑centric interfaces that followed. It contrasts the era’s hopeful promise of democratized knowledge with the way corporate design later reshaped user agency, and calls for a revival of genuinely interactive, learner‑driven media in the present day.

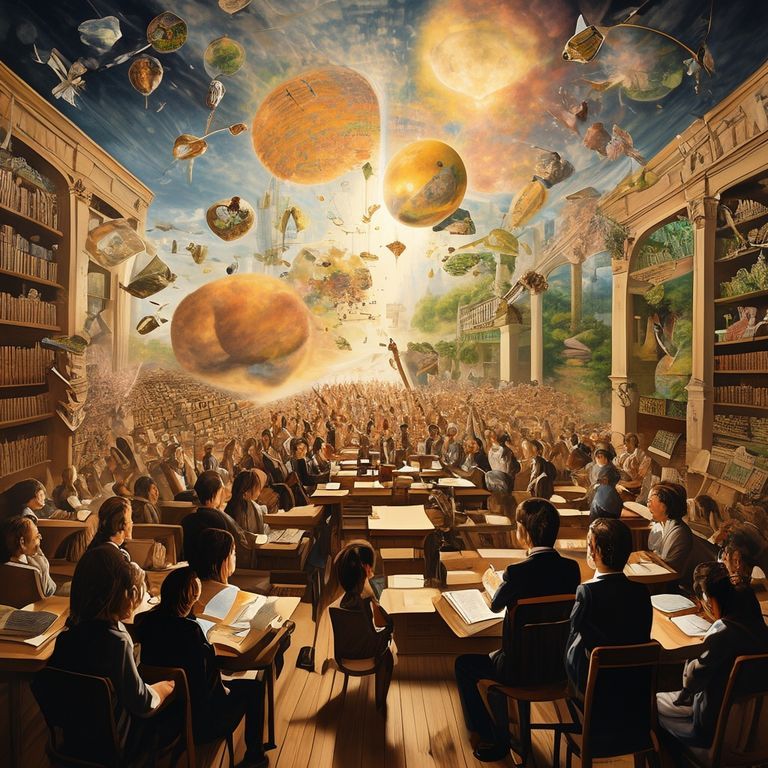

Utopian Scholastic was more than a stylistic flourish; it represented a cultural moment when the digital frontier seemed to promise an infinite, interconnected repository of knowledge. In the mid‑1990s, publishers and designers embraced a visual language dominated by bright, cropped photographs, flat colour blocks and minimal text hierarchy. The goal was clear: create a feel of optimism and forward‑looking possibility that matched the public’s growing trust in the Internet and CD‑ROM technologies.

This aesthetic found its fullest expression in educational products that rode the wave of the early web. Books such as Dorling Kindersley’s *Eyewitness* series and *DK’s* *Welcome to the Museum* leveraged high‑resolution images that were often removed from their original context to create dynamic, collage‑styled spreads. The clean white backgrounds and non‑linear navigation mirrored the interactive experience of early computer encyclopedias—Microsoft’s *Encarta* and the Macintosh’s *HyperCard*—which allowed users to hop from concept to concept without the constraints of a linear textbook.

The cultural resonance of this approach can be traced back to earlier media that anticipated the information‑dense, “click‑heavy” world that would soon dominate. The 1990 film *Hyperland* (directed by Douglas Adams) featured clean interfaces and interactive thumbnails, foreshadowing the way knowledge would be packaged in the era when personal computers were becoming household staples. That same spirit of exploration is evident in the puzzle adventure game *Myst*, which positioned players as solitary wanderers in a richly constructed world that blended visual storytelling with environmental puzzles.

What set Utopian Scholastic apart was not just its aesthetic but its underlying philosophy: the belief that technology could flatten geography and democratize learning. Libraries were no longer merely repositories; they became launchpads into virtual worlds. Students could browse a CD‑ROM encyclopedia as freely as a tourist wandering through a museum, with each page offering pathways that encouraged exploration rather than memorization.

However, the very ubiquity that made Utopian Scholastic attractive also made it vulnerable to corporatization. As the Internet matured, the design ethos that had once championed user agency slid into a more restrained, corporate‑friendly style dominated by minimalism and flat gradients. This shift can be seen in the transition from the photograph‑rich collages of the 1990s to the “Corporate Memphis” aesthetic that prioritizes branding over user autonomy. The same pressure that once made encyclopedias interactive now makes interfaces designed to nudge users toward monetizable actions.

The erosion of agency is also evident in the evolution of user interfaces from the early Windows 95 menustructure—where users could explore hundreds of dialog boxes—to the modern LLM‑driven search engines and recommendation systems that curate content for a corporate model. A 2025 MIT study highlighted that users of LLMs and search engines retained less information than those who wrote essays, suggesting that outsourced cognition diminishes learning.

Yet despite these setbacks, the core idea of interactive, curiosity‑driven learning endures. Modern titles such as *Civilization*, *Kerbal Space Program*, *Zachtronics* games, and open‑world mods for *Minecraft* demonstrate the enduring power of blending knowledge with play. They offer opportunities for research, critical thinking and problem‑solving that align with the spirit of Utopian Scholastic.

The personal narrative behind the article—rooted in memories of a public library’s music and software sections, childhood exploration of encyclopedias, and the thrill of early computer games—illustrates the emotional resonance behind the aesthetic. It reminds the tech community that at its best, design can kindle a sense of wonder and self‑direction.

Moving forward, the challenge is to reclaim the user agency that was central to Utopian Scholastic while leveraging today’s powerful platforms. Open‑source educational tools, community‑led wikis, and decentralized knowledge hubs like Wikipedia and GitHub show that it is still possible to build inclusive, participatory learning environments. By prioritizing design that invites exploration and by resisting the default path toward passive consumption, the industry can revive the principled optimism that defined Utopian Scholastic.

In closing, the Utopian Scholastic era serves as both a nostalgic milestone and a blueprint for the future. It reminds us that the best educational experiences are those that empower users to construct knowledge on their own terms, while ensuring that technology stays a tool—not a gatekeeper—in the pursuit of discovery.